MachinePix Weekly #12: Ben Krasnow, Applied Science; senior staff engineer, Verily

Ben Krasnow on designing biotech equipment and running a hugely popular YouTube channel. This week's most popular post is... worm grunting? 🐛😬

This week I sit down with Ben Krasnow, the Senior Staff Hardware Engineer at Verily, Alphabet’s life sciences company. He is also the man behind the wildly popular Applied Science YouTube Channel 🤓🧪

The most popular post last week was worm-grunting sticks, demonstrating yet again that sometimes the simplest machines are the most fun. As always, the entire week’s breakdown is below the interview.

I’m always looking for interesting people to interview, have anyone in mind?

—Kane

Interview with Ben Krasnow

Coincidentally, you know Jeri from the last interview because you both worked at Valve! How did you make the change from gaming hardware to biotech hardware?

I actually started in MRI-compatible computer peripherals: if you’re a researcher and you need someone in an MRI to interact with a computer, I made hardware to do that. It’s pretty cool—the biggest challenge is ferromagnetic materials. If you have any steel parts, even a single screw, the strength of the MRI’s magnet can launch it across the room. Any components with wire coils or anything could be induced with currents and get pretty dicey. You can shield your components, but the shields will catch a lot of eddy currents and heat up. A lot of times you have to use fiber optics where you would normally use wire. A lot of peripherals I made for MRIs were mice and keyboards and joysticks and those sorts of things, so funnily enough not that different from gaming.

When Valve found me, they wanted unusual feedback no one had done before like galvanic feedback and stress sensing, so there was some overlap from biotech.

What is it like being a mechanical engineer for a biotech company?

I would say the biggest thing to learn is that healthcare is often broken due to financial problems, not due to engineering ones. If you want to build something new it’s not as much a question of technical difficulty as it is a question of regulatory difficulty. At Verily, I get to work in the skunkworks lab, so I get a lot of intellectual latitude—but we try really hard to push down the cost of healthcare.

What are the coolest projects you’ve worked on at Verily?

I’m pretty excited about the one I’m working on now! You may have heard stories that dogs can smell cancer and corona virus infections. Last year it was in the news that there was a woman who could smell her husband had Parkinson’s. So obviously there are molecules coming out of the body that indicate some disease.

Dogs' noses are exquisitely sensitive. They can detect things in parts per trillion. Using dogs’ and peoples’ noses is not a scalable solution, and we’re working on addressing that.

What are the machines we use to benchmark dogs’ noses?

The gold standard is GCMS (gas chromatography mass spectrometers). They’re very expensive, very hard to set up. You need a trained technician to use them. Smell samples don’t travel well either! It’s best to get the person and machine in the same room. All these make developing smell-based detection challenging. We’re trying to change all that.

I love the Applied Science channel! How did you start this?

It was in large part kicked off by Maker Faire 2011. Each year you came up with a better and better project, and this was back when Maker Faire was still mostly home-built projects. I had an idea to build a scanning electron microscope, and that’s when I also made my first video. Jeri’s channel was actually a huge inspiration, she was one of the first hardcore technical channels.

How do you decide what to film for Applied Science?

It was a different world in those days. In 2011 and 2012 there wasn’t as much money to be made on Youtube. We were doing it for the hobby experience and the attention. I was trying to come up with more and more extravagant projects. I did a DIY chip fab, liquid nitrogen generator… it kept getting more extravagant. Now, I get inspiration from conversations with friends or coworkers. If something comes up and I wonder “huh, how does that work?”—that becomes an idea for a video.

As a camera nerd, I’m curious what you use to film your videos.

I use a Panasonic GH5 with a Sigma 18-35 f/1.8 lens with a speedbooster. I shoot B-roll from a tripod while I work, and try to do the A-roll in one single take from a tripod.

Do you use the things you make?

They’re fun proof-of-concepts. The electron microscope I made has a worse resolution than an optical microscope, but they’re fun to make. My projects and videos are anti-work, it’s nice to just have a non-commercial outlet.

Most favorite thing you’ve made for the channel?

My favorite is still the electron microscope because it’s foundational. A more recent favorite is a video of a record player needle using the electron microscope!

I forgot to mention the cookie machine. It dispenses tiny amounts of each ingredient so that the recipe can be varied for each cookie on the sheet. It tests variations faster with with less ingredient waste.

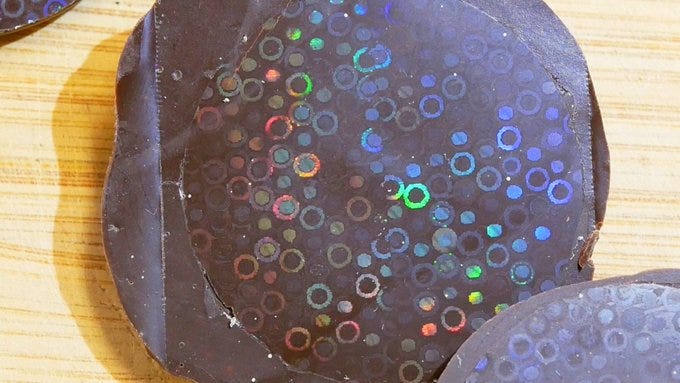

I also transferred edible holographs to chocolate.

What are your other favorite channels or accounts (besides @MachinePix of course ☺️)?

That’s a good question: NileRed, has a hugely successful chemistry channel with awesome videography. He has one reaction in particular which is a petri dish that spontaneously generates these waves. It’s totally crazy.

Tech Ingredients is a really good channel. Huygens Optics too: he's making his own chip fab and has his own wafer stepper!

Any side projects you’re working on right now?

I’ve had a hydraulic press in my shop for a while. I want to make a 100,000 PSI espresso! I’ve got it to 60-80K, but there are a lot of challenges. The gaskets just blow. At those pressures, solids behave weirdly. Aluminum parts squeeze out like toothpaste. I don’t think it will taste good—it’s designed to get views on YouTube, but i’m still excited to try it.

What’s your favorite simple (or not so simple) tool that you think is under-appreciated?

Probably the old stereo inspection microscope. People think you use a microscope for small stuff, but they’re great for everything. I think they’re like $350 now, it lowers eye strain a lot. It’s the center of my shop, I do a lot of work under it.

I actually asked a watchmaker why they still use eye loupes and not stereo microscopes, and he didn't like the question very much. I think it’s a tradition thing. I think if they sat down and used a stereo microscope they wouldn't go back.

The Week in Review

The even crazier version is the machine that vacuum-packs entire foam mattresses.

This week’s most popular post! Also known as worm fiddling or worm charming, I thought worm grunting was the funniest phrase. The stick in the ground is called a “stob”, and the stick used to rub the stob is called the “rooping iron”.

If you still haven’t gotten enough of worm grunting, be sure to check out the Annual Worm Gruntin’ Festival.

This is floating around on the internet captioned as a hydraulic press, but it’s almost certainly a screw press for safety and simplicity (and by just looking at it…). This is a much more confidence-inspiring setup compared to this terrifying gravity drop forge.

If you’ve ever wondered why commercial ice has little holes in it, this is why: it’s a consequence of a machine design—not an optimization of the ice itself. Vogt introduced the first commercial tube ice maker in 1938.

Postscript

This past week I fermented makgeolli, a very tasty Korean alcoholic beverage that kind of tastes like a boozy, fizzy horchata. It’s extremely easy to make and requires no special equipment!

If you enjoyed this newsletter, forward it to friends (or interesting enemies). I am always looking to connect with interesting people and learn about interesting machines—reach out!

—Kane