MachinePix Weekly #22: Simon Winchester, author of The Perfectionists

Simon Winchester talks about precision engineering, his framework for consistently writing best-selling history books, and naming donkeys. This week's most popular post was explosive quarrying 💥🪨

This week I sit down with Simon Winchester, a New York Times best-selling author and Officer of the Order of the British Empire with bylines in Condé Nast Traveler, Smithsonian Magazine, and National Geographic.

While this is a bit of a break from the engineers I usually interview, Simon’s book The Perfectionists: How Precision Engineers Created the Modern World answers a question often asked by engineers when they start feeling existential, usually many hours into debugging a machine: if we need precision machines to make precision machines, how did we bootstrap precision?!

Under its British title Exactly, The Perfectionists was short-listed for The Royal Society’s Science Book Prize, the most prestigious prize in the field. It’s one of my favorite non-fiction books and I highly recommend it. Simon’s upcoming book Land: How the Hunger for Ownership Shaped the Modern World looks to be a delight as well.

The most popular post last week was multi-row blasting for quarrying or open-pit mining. If you are, ahem, a perfectionist, you’ll notice a few that fail to detonate and never be able to unsee it. As always, the entire week’s breakdown is below the interview.

I’m always looking for interesting people to interview, have anyone in mind?

—Kane

Interview with Simon Winchester

You started your career in geology and mining; what prompted the switch to writing?

The lazy thing for me to do would be to send you to The American Scholar, which is my very brief essay on the person who told me to transfer my career. My wife and I were cleaning the attic a week ago and found a box of miscellaneous papers. In it was this tin which contained biscuits once upon a time. On top of it was this letter from 1966, dated to me from Wales to my tent in Uganda from a chap called James Morris, who I’d asked how to be a writer, and he told me to go into journalism. James then was famous for being the journalist that made it to the top of Everest in 1953. That was how it all happened: I was not a particularly good geologist and became a journalist.

He changed my life, and then he changed his ten years later by becoming a woman. James Morris became Jane Morris, and she and I wrote a book together. I found those letters Wednesday of last week and I vowed to ring Jane to tell her. So I rang her number in Wales and there was no answer. I called three times and no answer, which I thought was most peculiar. One of my children then rang from london and informed me Jane had died, so that's why I got no response.

I reached out because The Perfectionists is one of my favorite books, and answered a question that’d always bothered me: how did humans bootstrap precision? What inspired you to write the book?

A man called Colin Povey wrote me out of the blue. I had written a number of books, and the immediate predecessor had been on the United States and the people, whether they be map makers or surveyors or builders, that had knit this country together. This man Colin who was a scientific glassblower in Florida had read the book and wrote me to tell me I should write a book on the history of precision. I was writing a book on the Pacific Ocean and thought “maybe.” I put it to my editor and she said unless I came up with a specific structure it may be a little niche and hard to do.

I’m a firm believer, in nonfiction anyway, that there are three key elements: first the idea, then second thing you’d think would be important would be fine writing, but in my view it’s not. The second thing is structure—and then if you can write it nicely that’s lovely. Take for example how I wrote about the Atlantic Ocean: when I tackled that ten years ago, I was crossing the ocean and reading an anthology of Shakespeare poems by David Owen, a former British Foreign Secretary—he had included his chosen poems according to Shakespeare’s Seven Ages speech from As You Like It. Those seven ages could be applied to an ocean! The Infant: how it was created; The Soldier: what wars were fought on it; The Judge: the laws of the sea, etc. I always try to choose an interesting and unusual structure, if you like.

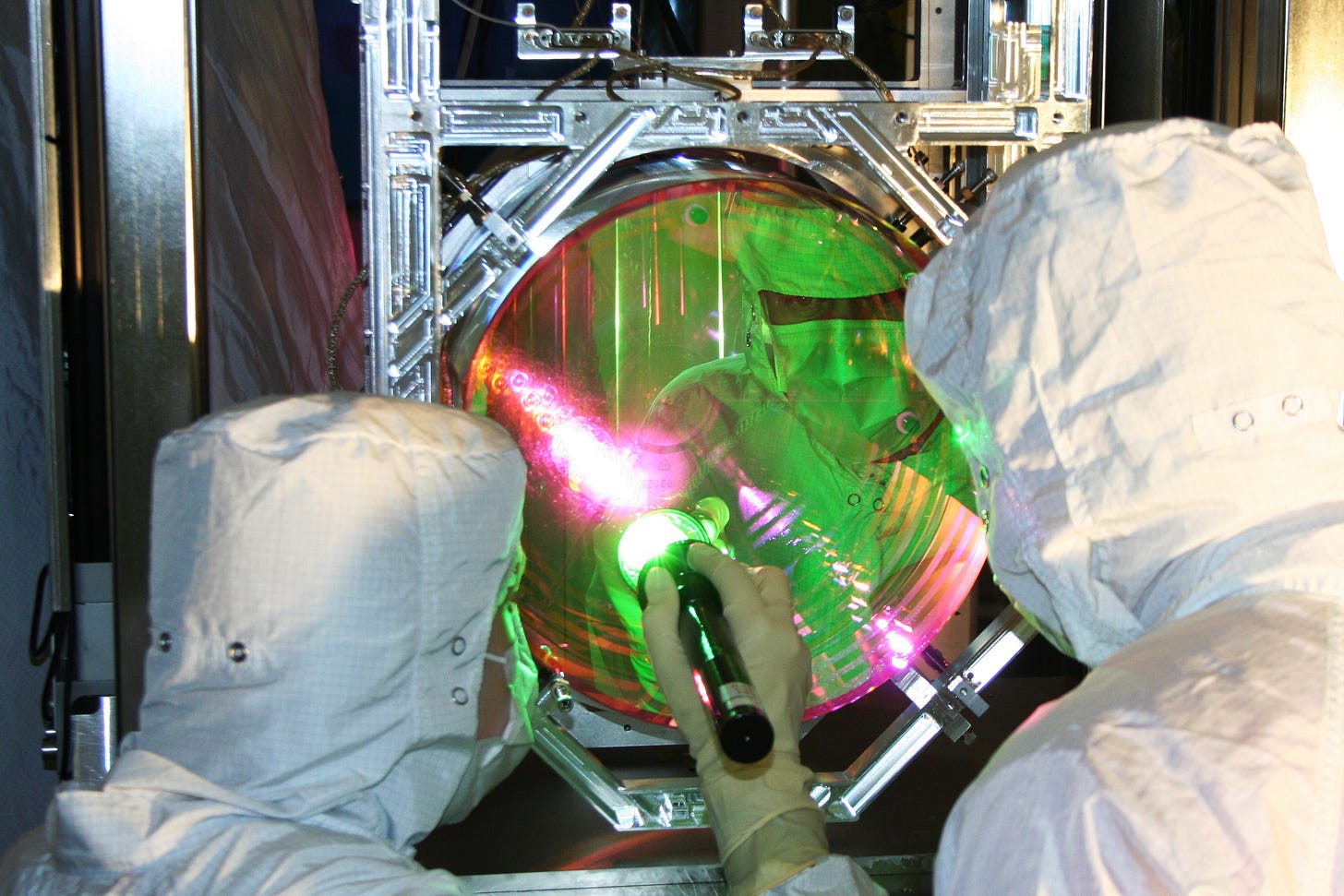

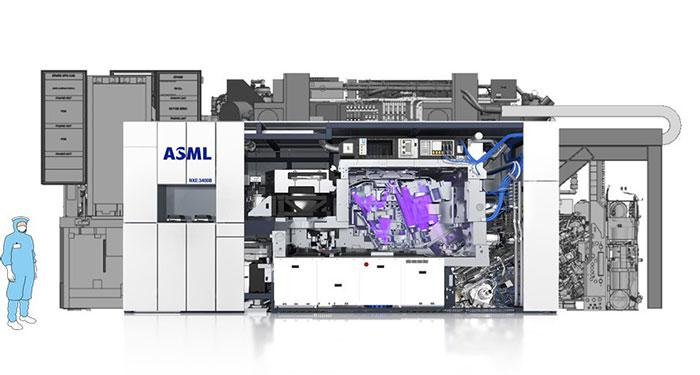

The structure [of The Perfectionists] I came up with was the one you would've seen. The progression of every step of precision through the chapters, starting from the tolerances from a tenth of an inch, which was the distance between the inner surface of a cylinder and the outer surface of the piston of James Watt's steam engine in North Wales, all the way up to the LIGO (Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory) and the phenomenal degree of precision you see now, not least of all in the manufacturing of semiconductors. For The Perfectionists, this particular structure seems to have worked. Once my editor Sara Nelson had seen that she said “let’s do it then.”

What was the most unexpected thing you learned while researching The Perfectionists?

There are many. I should go back and tell you about Colin Povey. Once I had accepted his suggestion about writing a book, we were in correspondence for a long time. We never met until the beginning of the book tour. In the audience in Washington DC was Colin who had come up from Florida because the book in his way was his baby. He brought me a present! He’d blown me a glass Klein bottle, and I thought it was so wonderful. I used it as a prop on the rest of the tour. I would end my talks with “there is nothing straight in nature. Things need not necessarily be precise to be beautiful,” and would hope for thunderous applause.

But back to the question. You’d asked me about something unusual. Off the top of my head, I loved the story of Joseph Bramah and the lock he created in the later part of the 18th century and put in his window front in Piccadilly in the West End. He put the lock on a pillow and said anyone that could pick the lock would win 200 guineas or about 200 pounds. No one opened it by the time he passed away, and his son took over the business.

It was still unpicked during the Great Exhibition of 1851 at the Crystal Palace about 70 years later, where a man came forward and said “I can pick it.” He was Alfred Charles Hobbs from Boston, and he had invented the Parautoptic lock; he claimed his look was unpickable and he could pick the Bramah lock. He worked on it for something like 60 hours and got it open. The Bramah Lock Company said “fine you’ve done it, here’s your 200 guineas, well done, we don't feel like our reputation is sullied because there aren't burglars that are going to work on a lock for 60 hours.” Regarding Hobb’s Parautoptic lock, someone in 1855, with two simple chopstick things, opened it in fifteen minutes. That was Linus Yale. You probably have a Yale lock on your door. I do.

What’s your favorite chapter or anecdote from The Perfectionists?

I think the thing that interested me most of all was the one on semiconductors, and also LIGO and the ASML lithography machines. They’re amazing machines, I went to see them in Holland. They were just incredible. I found that for me, the boundry pushing part of the story was my favorite. I think I got more excited by it as I got closer and closer to the present.

The whole chapter about time and GPS control in Colorado was also great. That’s the best thing about nonfiction: you learn a lot on the way. I didn’t think this book would do particularly well, but it did.

The book got existential towards the end with ASML and LIGO chapters. Where do you think humans go with precision? Are we over our skis?

Very interesting. I’m looking [on my desk] for this publication, Lapham’s Quarterly. Are you familiar with it? The next issue is about Democracy, but the next issue after that is on Technology, and they’ve asked me to write the lede, the thematic essay. I’m dealing with this question of technology and ultimately if the reliance on it will create a dystopian or utopian society. I made notes a few minutes ago actually, at the moment I’m of two minds—not least because the book that comes out on the 19th of January is on the history of ownership of land. I did a lot of research: Maori communities, indigenous communities in Australia, Native American communities, Polynesian communities—their reliance on technology is minimal, but their success in things like happiness is pretty high. One has to wonder, if one could choose an invention that’s been utterly transformative, it’d be the transistor. Another would have to be the nuclear weapon. Of course those are two very different things. Ones gives us the iPhone and the ability to communicate over distance. The other is quite the reverse, so I am split. It’s easy to look back on technological breakthroughs like the railway and how fast someone was killed by it. There’s a lot going on in my mind at the moment so I’m having to balance this virtual book tour for Lands and writing this essay for Lewis [the editor of Lapham’s Quarterly], which I hope is up to his standards.

Very timely, I’m actually reading The Making of the Atomic Bomb right now.

Yes, a great book. Took him so long to write. A shame he followed it up with a dreadful book.

How do you choose topics for the books you write?

In the early days, the trajectory of my career was that I was a journalist that wrote books until 1996, when I was living in Hong Kong and I wrote a book on the Yangtze River. Like most of my books then, it was well reviewed but didn’t sell particularly well. This was beginning to worry me because in 1997 I was 53 and I was thinking younger and more energetic and prettier people were writing books. I was wondering where this would lead me—I didn’t want to go into PR or anything ghastly like that. I stumbled into writing this book on the creation of the Oxford English Dictionary, no one thought it would do well. HarperCollins only printed 10,000 copies I think, but it was a hit and that unexpected success completely changed me.

What happened then, the editor, a chap called Larry Ashmead, sat me down and said “this book has been very successful. Why? I think it’s because it’s about a previously unknown person that made a major contribution to humanity, has a story with ups and downs, and he was involved in grotesque bodily mutilation.” When William Minor was in an institution outside of London he cut off his penis and threw it in a fire because he thought it was the source of all his problems. He asked me if I, Simon, would know anyone else that would tick all those boxes.

I thought about the Arctic expedition of Adolphus Greely and 25 men who were lost and effectively forgotten about. The US Navy couldn’t retrieve them the first year because of ice. Then there was a presidential election and the Navy forgot about them. They were marooned for three years. Six of the 25 survived. When the survivors were brought back, Adolphus Greely was considered a hero until people found out about the cannibalism. I had the diaries, I tracked down the route of the expedition—I thought it would be a great book, it checked all the boxes. But then I was doing some research, and all the papers I wanted in the Library of Congress had been looked at by someone else. The librarian wasn't supposed to tell me, but told me it was this gentleman from Richmond, Virginia. So I rang him up and he said “I’ve been working on this for 25 years, please please don’t do the book” and I promised him I wouldn’t. So then I rang up my editor and told him what happened. He said that’s a shame, weren't you a geologist? Anyone there? I said yes, and remembered this gentleman named William Smith, the first to make a geological map. So I looked him up, and there were these sentences that whetted my appetite. His maps were plagiarized, he went bankrupt, his wife became a nymphomaniac—this is brilliant! So I called my editor, and we did Smith and that book did great.

That led to a couple more geology books. Eccentric and weird scientists led me to Joseph Needham, who is one of my heroes. He was a chemist, born in the 1900s, died in 1995. Tall, good looking, charismatic, chain smoking, nudist, socialist, womanizer, married to a Chinese woman and became obsessed with the history of Chinese science. He wrote a 25 volume series, a monumental accomplishment, and I wrote a book on him. That got me interested in biggish topics: the Atlantic, the Pacific, the Perfectionists, Land, and soon, if my publisher agrees, on Knowledge, the spreading of what we know. Sometimes there’s a link from one book to another, sometimes it’s just a delight in big topics and trying to corral them into a readable form.

What happened with the expedition book by the guy in Virginia?

He sold about 100 copies. So sad. All that time and effort and the book went nowhere.

What’s up with the capybara on your website?

According to my late mother, she insists that was the first word I ever said. There's a zoo to the north of London called Whipsnade and she took me there one day. She pointed to this big friendly rodent and said “this is a capybara” and I said “capybara?” and it became a joke in the family. I had a company called Capybara in Hong Kong and on my business cards back in the day. I thought of having one here but it’s too cold.

My ambition, but my wife is religiously opposed to it, is to have two donkeys. Mainly, so I could name one Otie so I could tell my bookish friends “this is my donkey Otie.”

Any side projects you’re working on right now?

Well, I do a bit of woodworking, and I'm not very good, but I try. So when I finish a chapter I go do a mortise and tenon and try to make it good looking. What else do I do? I was a very keen bee keeper but bears tended to eat them. And letterpress printing. And stamp collecting. As one gets older, you focus on a smaller and smaller area in stamp collecting. I’m focused on stamps from Hangkow, now Wuhan these days.

What’s your favorite book?

Without a doubt, by George Perec, called Life: a User’s Manual. Written in the 1980s in French, translated into English. I just think it’s the most magical book in every way imaginable. He was also famous for La Disparition, or A void in English. In both French and English versions, he doesn't use the letter “e” in the books.

What’s your favorite simple (or not so simple) tool or hack that you think is under-appreciated?

All I will say is that the way I write books, this is hardly clever, but some people find it useful: at the top left hand side of my screen I put the day I started, the day the contract is due, the number of words I’m contracted to write—in the case of Land, that’s 250,000—so each day I track how many I wrote and if I’m behind or ahead. If at the end of the week I’m ahead, I can take a day off. As a result, I’ve thus far never missed a deadline. That is my little conceit to length and time. It’s something in a way that derives from my newspaper career. If you’re covering a battle in Calcutta or Belfast or something like that and they say “1,000 words by 10 PM,” you have to or it doesn’t make it into the paper. Sounds very fascist but it works for me.

The Week in Review

I’ve seen spider excavators and telescopic excavators, but these winch-assisted excavators look next-level crazy.

It took ten tries for the SpaceX Falcon boosters to land correctly, and now we don’t even blink when they land three-at-a-time. I’m excited to see how Starship progresses. Other idioms for crashing: lithobraking (braking with the ground as opposed to aerobraking) and controlled-flight-into-terrain (specifically when a pilot has control but crashes).

Neat.

I’m conflicted about posting these videos with terrible safety practices. Please wear the necessary goggles, masks, and flame retardant equipment!

Postscript

Next week I’ll be guest-editing The Prepared, an excellent newsletter by Spencer Wright on logistics and manufacturing.

If you enjoyed this newsletter, forward it to friends (or interesting enemies). I am always looking to connect with interesting people and learn about interesting machines—reach out!

—Kane